Parallel efficiencies of (small) plane wave DFT calculations

Plane wave DFT calculations are often known as “cubic-scaling” where the cost grows as the number of atoms (more precisely the number of electrons) cubed. Thankfully, they can be parallelised over many (possibly very large number of cores) to accelerate the calculations. This is often done at multiple levels: the plane wave coefficients, the bands and the k points.

A frequent question one may ask when running calculations is: how many cores should I use? Obviously, using more cores should make the calculation faster, but it also increases the time spend on inter-process communications, causing the parallel efficiency to drop with increasing core counts. It not uncommon to see examples where a single calculation can be parallelised over thousands of cores for a supercomputer with relatively small drop on the efficiency. However, the rate of reduction in the parallel efficiency is also highly dependent on the size of the system: those of hard problems (e.g. more atoms) drop much slower than simple and small systems.

If there are many calculations to run through, rather than getting the result of each calculation quickly, it can be more efficient to run multiple calculations in parallel, each using a smaller number cores to achieve a higher throughput.

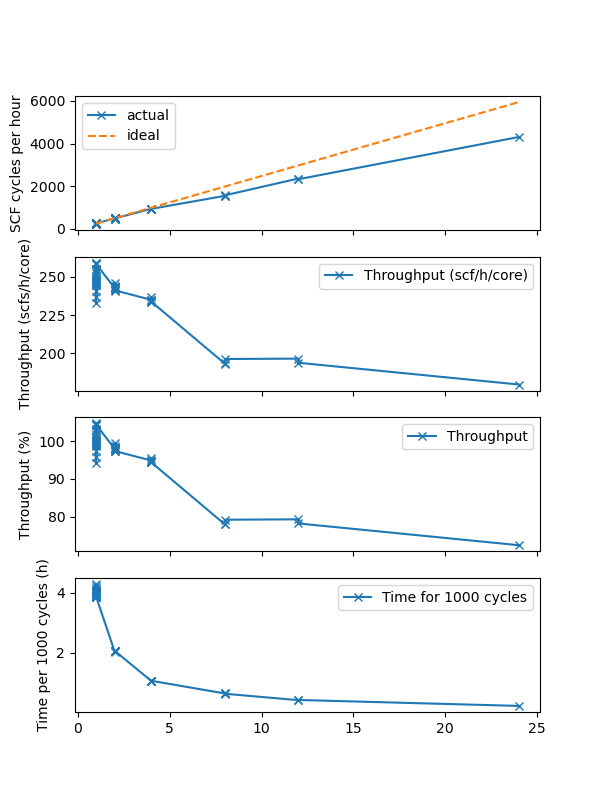

Below are some test results for a 28-atom structure using the code CASTEP with increasing number of cores while maintaining a full population of single compute node with 24 cores. This is a “small” calculation with only 340 eV plane wave cut off energy and 4 kpoints, and 106 bands.

As one may expect, the parallelisation efficiency drops with increasing number of cores. By running 24 cores jobs instead of 1 cores, the overall throughput has dropped to about 80 %, while running six 4-core jobs has only a 5% lost in efficiency. While running many “small” jobs does increase the overall throughput, it comes at the cost of very long “time-to-result” for each calculation. In reality, computing clusters often have cap of run times, and having long-running time for each calculation risks having unfinished ones getting killed, wasting a certain amount of time and resources. This also means that the aftermath of having any kind of node failure will be higher, as calculations have longer turnaround.

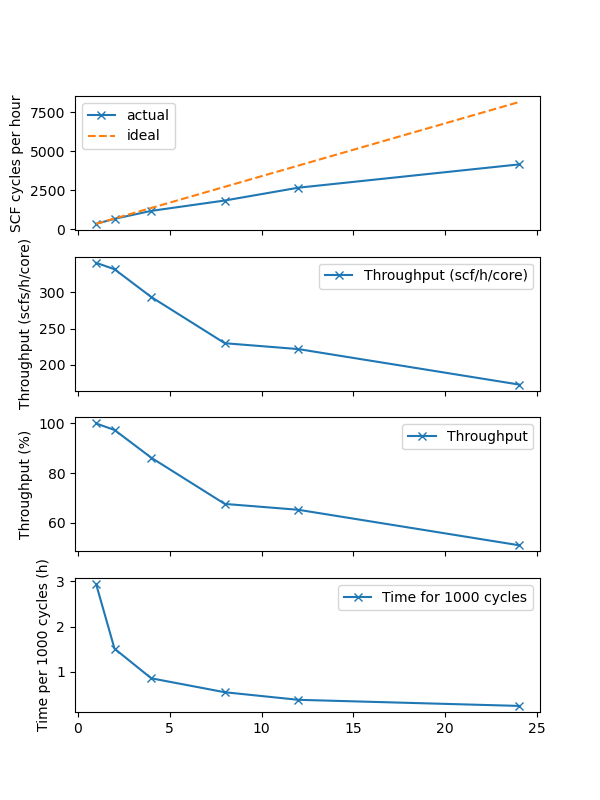

One important note is that if the node is not fully occupied in the tests, the benefit of running smaller but and many jobs can be significantly exaggerated, as shown in the plot below.

Several factors could cause this. First, under populating the node means each MPI process has access to more memory and communication bandwidth. Second, modern CPUs often boosts the frequencies when only a few cores are active to be able to utilise the thermal headroom left by the idling ones.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: